Getting a Peek into Medieval Life. By Way of Southampton.

When I lived in England, I got to go to a lot of really cool places. We were members of both English Heritage and the National Trust, the two organizations that operate 98% of interesting historical sites in England, and we took advantage of those memberships on an almost weekly basis. We visited huge places like Dover castle, famous ones like Stonehenge, and grand ones like Canterbury cathedral. But perhaps my favorite site of all is neither huge nor famous nor grand. It’s this place:

You can visit lots of cool sites around England and be awed by how they look. But they don’t often give you a great sense of what it was like to live there. What people did and how they spent their days and interacted with one another and all that. And yet, once your characters come home for the night and kick off their manure-encrusted boots, how they live their lives matters if we want to feel like we’re a part of it.

It’s too easy to create places that are essentially just modern equivalents with a veneer of ye oldeness. Our inns and taverns tend to be based on modern bars. Need a sword or a wand of magic missile? No problemo; just hop on down to the sword or magic shop. OK, it doesn’t look like a Wal Mart, but it probably looks like the shops in your local strip mall, with a little extra thatch on the roof for color. Our characters order off the menu at the tavern, our buildings and towns are well lit at night.

But thatch and firelight are not the only differences between the then and the now. The people of earlier years were not like The Flintstones, living just like modern people but with everything made out of rock and animals. Medieval folk—and the Romans and Victorian folk and those living in the Iron Age and the times of the Celts and the Saxons—actually lived differently. They interacted differently with the world around them and the civilization they built.

If you want your setting to feel a bit more authentic than an episode of Gilligan’s Island, a little insight into how folks actually lived their lives is really helpful.

So Let’s Visit this Medieval House

The Southampton medieval merchant’s house is, well, a house that belonged to a medieval merchant. A wine merchant, in this particular case, as you might gather from the signage. It was also a shop, because that’s how they rolled in those days: A merchant or tradesman worked out of his (or sometimes her) home, with a room in front for business and perhaps some storage space for extra stock if that stock tended to use up much space. Although it’s hard to see in the photo above, there’s a large window underneath that overhang; a big shutter closed the shop up after hours, but opened horizontally to create a counter onto the street during business hours. Behind that is a smallish room that served as the shop itself. The rest of the building is the house (expect the cellar, which was mainly used to store wine).

It dates to the late 1200s, and it’s pretty typical of city homes throughout Europe for a period of six or seven hundred years if not longer. It’s the original building, although it saw many uses over the centuries and had to be restored back to its current (medieval) condition.

(Incidentally, the merchant’s house isn’t the only authentic peek into medieval life in England. The clues are all over the place, if you know where to look for them. The roads of virtually every town and city follow the same plan they did in the Middle Ages. Heck, take the A3 into London, and marvel not just at the twists and turns as you approach the city center, but also at how the road shifts from four lanes to two and then back to some ill-defined three-and-a-half lanes, and so on. That’s quality medieval urban planning, right there.)

The merchant’s house isn’t a dazzler of a site. It’s not big and it’s not grand and it doesn’t draw a huge crowd of tourists, and that probably explains why English Heritage only bother to open and staff it a couple of days a month. But it is fully restored and fully furnished, and, unlike the echoing, empty chambers of most castles—or the treasure-filled galleries of stately homes—it gives you a genuine sense of what daily life was like in an era that’s almost unimaginably different than our own.

For starters, the layout isn’t what you’d come up with if you sat down with your graph paper to lay this place out for your D&D game. Like a castle, the principal space is a great hall—a big room that serves as living, dining, and lounge space. In this case, the hall sits in the middle of the building, a two-story space that extends to the open rafters above. A staircase leads to a gallery, which connects to the front chamber (above the shop) and the rear chamber (above the kitchen, which sits at the back of the ground floor).

The thing that struck my most about the medieval merchant’s house is the utter lack of climate control. The windows don’t close; they’re open spaces barred with wooden slats for security. Where the rafters meet the walls there’s a six-inch gap between the top of the wall and the roof, all the way around the building. The place would have been drafty and cold whenever the weather outside was. I noticed the same thing in many of the castles I visited. The truth is, a medieval building was more like a permanent tent than a modern home. It kept the rain off your head and warded the worst of the wind, but that was about it.

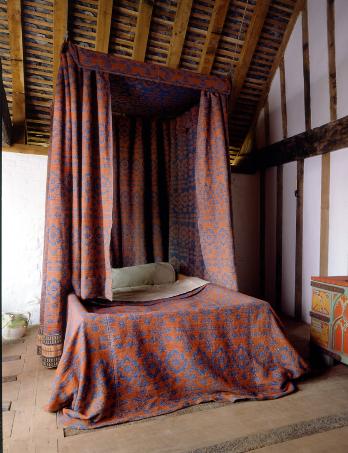

You know those big old-fashioned beds with curtains all around, like the curtains Scrooge shivered behind as he attempted to hide from Christmas ghosts? That wasn’t just the style at the time—it’s how people kept from freezing to death. A fire couldn’t be left blazing unattended while people slept—even if you could afford the firewood, that was just asking for a catastrophic fire that might take out the entire city (which happened every couple of decades as it was). So the medieval house was cold at night. And dark—there wasn’t a light switch to flick on when you heard that ghost shuffling around. This is exactly the kind of insight that will help you immerse your audience in your world!

The medieval house also didn’t have much in the way of security. And by much, I mean anything. Most houses had no locks. But that really didn’t matter, because the house was probably not left unattended very often. The business was in the house, families were large, and anyone in the middle class or higher probably had a servant or three. The unglazed windows were barred, and the doors could be bolted from the inside for security at night. Things of particular value were kept in a large, heavy chest in the kitchen, and that might have a lock. But most of the time security was provided by the simple fact that someone was always home.

(As an aside, another good place to visit is Dover castle. (There are a million great reasons to recommend Dover; this is just one of them.) When I first moved to the UK the keep was a big mostly-empty building you could wander through, like the majority of castles across the UK, but while we were there they completely redid the interior as it was in the era of Henry II (earlyish Middle Ages; the period of the Crusades and Robin Hood). It’s a bit more opulent than the merchant’s house, but the kitchen and chapel and other workaday areas are also done up in this manner.)

What’s This Mean to the Historically Minded?

So if you’re writing historical fiction (or playing a medieval fantasy game) you gotta appreciate that the medieval world doesn’t just feature different buildings. (In fact, it doesn’t necessarily feature different buildings at all: Go back to that first picture from Canterbury—see the word “coffee” on the building to the right? That’s a Starbucks. Seriously.) If you want to bring your world to life—if you want it to feel real—it’s not enough to stock it with timber framing and thatched roofs. It needs to feel like the different—even foreign—place it really is.

A stable isn’t a garage; it’s a place where animals are fed and cared for, where their medical needs are seen to, where they poop and have babies and where they sometimes die.

An inn isn’t a restaurant or a roadside motel. There’s no menu—you eat what they’re making that day and you sleep where they have room.

Even houses aren’t much like what we think of them. Discover the details that give them distinction, and make those details matter in your story.